Improvement Process

Overview

The Unsignalized Intersection Improvement Guide (UIIG) is prepared to assist persons within the agency responsible for addressing problems at unsignalized intersections within their road network. The problems can be related to deficiencies in safety, operations, or access for the various users of the intersection—motorists and non-motorists alike. The identification of the intersection problem and implementation of the most cost-effective treatment should follow an improvement process regardless of the size and capabilities of the agency, from the smallest village or town to the largest city or county. That improvement process should be iterative and continuous and include the following steps:

- Identify the problem location(s).

- Analyze the location(s) to quantify and characterize the problem.

- Identify potential treatments that may address the problem.

- Select and implement the most affordable cost-effective treatment(s).

- Monitor over time and evaluate the effectiveness of the implemented treatment(s).

Additional activities may be required within each of these five steps, depending on the type of improvements being considered.

1. Identify the problem location.

For agencies to address a problem, issue, or concern on their roadway networks, they first need to be aware that a problem exists. Agencies need to develop a means to monitor their intersections (as well as their entire road system) to determine if improvements are needed. Problem identification is a necessary precursor to addressing safety and operational deficiencies and a critical component of minimizing potential tort liability. Agencies cannot simply “look the other way” or claim ignorance. Even if the agency does not receive explicit notice of a concern or problem, the fact that a deficiency existed for a significant period of time may constitute constructive notice, because the agency should have been aware of the issue.

A traffic problem or roadway deficiency may exist at a specific unsignalized intersection, at several unsignalized intersections along a corridor, or at numerous unsignalized intersections throughout the jurisdiction. An agency responsible for the streets and roads may become aware of such problems in several ways:

- Issues brought forth by the public, especially those who travel the roads frequently, such as school bus drivers, mail delivers, etc.

- Observations during police patrols or crash investigations.

- Unscheduled observations or systematic monitoring of the roadway by personnel within the agency responsible for the road network.

- Periodic review of crash data aimed at identifying high-crash locations.

Input from the Public

Public feedback is a common mechanism by which an agency is notified of potential problems at one or more unsignalized intersections. This method is more typical for low-volume or rural areas where traffic collisions are infrequent and crash data are less helpful in identifying locations where improvements would be warranted.

Public input is important to local agencies responsible for traffic control or street design decisions and should, therefore, be welcomed. The public can effectively serve as the “eyes and ears” of an agency, especially when an agency is understaffed or its jurisdiction is expansive. Means should be developed to encourage and facilitate public input and to process and investigate the information received.

Agencies have several ways to receive input from the public regarding traffic problems at unsignalized intersections and should seek out this information as a way to help monitor their roadway networks. Rarely would an agency create a citizen report form exclusive to unsignalized intersections; a more likely approach would be to create a process for soliciting and receiving citizen input for most traffic issues and other related public works concerns. These concerns may range from maintenance items (e.g., missing or damaged signs, overgrown vegetation, or potholes) to much larger issues (e.g., speeding or crash patterns). There are a variety of ways to allow citizens to report traffic issues—traffic complaint hotlines, direct telephone connections to agency staff, online reporting forms, and software applications (also known as “apps”) for mobile electronic devices that may even allow citizens to submit photographs of the condition along with their complaints. The hotline setup is often not preferred by agencies except for emergency conditions because it requires constant monitoring.

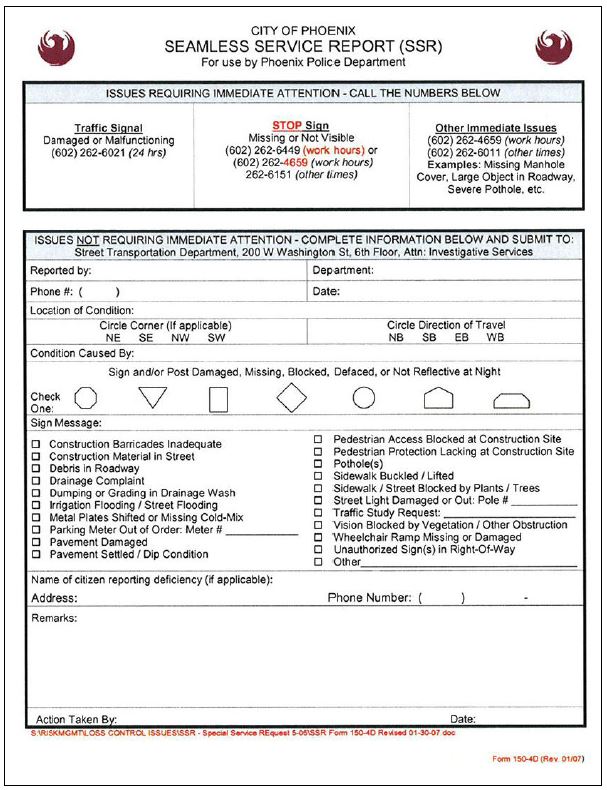

Example citizen complaint and service request forms from various agencies show some of the different online approaches that are used in gaining input from the public.

- The City of Tempe, Arizona has an online listing of forms for citizens.

- Another method of receiving input is to have a 3-1-1 page with various methods for contacting city departments.

- The Seattle Department of Transportation developed a multi-page form to guide a requestor through the process of reporting a damaged traffic sign or signal or other traffic issues. A hotline number is provided for issues that need immediate attention.

- The New York City Department of Transportation website has photos showing the types of traffic problems that may exist to help encourage the requesting citizen to use terminology consistent with the Department; the website also provides a selection of forms or requests an individual may want to make of the agency.

- The Town of Queen Creek, Arizona, City of Pasadena, California, Town of Fountain Hills, Arizona, and Town of Prescott Valley, Arizona utilize Citizen Relationship Management software for online citizen requests. (Note that some agencies require that respondents register prior to submitting feedback.) The company that provides this software also offers applications for mobile devices. This type of software integrates Frequently Asked Questions into the system, which has helped reduce the number of requests.

- The City of Prescott, Arizona offers a map-based reporting system for potholes. Users click on the map at the location of the pothole and fill in a form with their contact information and details of the issue. Previously-reported issues are shown publically on the map with submittal date and approximate location.

Forms or procedures for citizen input vary, but the best online forms are straightforward and simple to use and will prompt individuals to provide their contact information for agency follow-up. Citizens are often confused by technical jargon and simple issues such as cardinal directions. The online forms should also be easy to find on an agency’s website and easy to complete and submit. Including a limited number of check boxes on the form is one method to help simplify the concerns that are received, allowing the agency to automate the process to forward a complaint to the proper person or department (e.g., potholes would be directed to the public works department, while speeding complaints would likely be directed to the police department). Agencies that host these online forms must ensure they have a mechanism to review the submitted complaints in a timely manner. Citizens must be informed that emergency concerns (such as a missing STOP sign or large pothole) should be called in to a dispatcher or call center maintained by the agency.

The UIIG includes a generic Citizen Traffic Service Request Form for reporting traffic issues at unsignalized intersections (as well as other locations) that can be downloaded and modified to meet their specific needs.

After a traffic service request is received and investigated by an agency, the requesting citizen should be contacted and informed of the action that will be taken. This assures citizens that their requests have been considered and may encourage additional public input and monitoring. The traffic request forms and follow-up actions should be retained on file for future reference.

Not all problems identified by the public are legitimate safety or operational deficiencies. Nonetheless, if one or more members of the community, police, or public agency strongly believes an issue exists at an unsignalized intersection, then it should be investigated by the agency, and the investigation and resolution should be documented.

Police Patrols and Investigations

Police typically monitor roadways 24 hours-a-day, seven days-a-week and are involved in traffic crash investigations. Therefore, they tend to have a keen awareness of traffic issues and roadway concerns. While police officers are not trained as traffic engineers, they usually have sufficient knowledge to recognize when a location should be brought to an agency’s attention for further investigation. Agencies should encourage police to report traffic concerns to the appropriate agency staff responsible for intersection or traffic control or design and provide a convenient means to do so. A report form can be developed to receive input from an officer for all types of roadway and traffic issues—missing or damaged signs, potholes, damaged sidewalks, streetlight outages, lengthy queues and delays, etc.

Police should also be encouraged to report traffic concerns at intersections and other locations when conducting crash investigations. Issues related to nighttime illumination levels, traffic control, or intersection design that may have contributed to a crash should be reported to the appropriate agency department. An example is the Seamless Service Report form, shown below, used by Phoenix police for reporting traffic issues. A technique to garner continued police traffic input is to provide feedback to the reporting officers about their reported concerns and any remedial action taken or planned. Police supervisors should find a way to credit officers for reporting traffic issues for further investigation as a part of their daily work duties.

Inspections by Staff

Another source of information may come from periodic inspections or surveillance by agency staff. For an agency responsible for a large geographical area, it may be best to assign segments of its jurisdiction to specific individuals for periodic monitoring. In this manner, systematic monitoring of intersections may be conducted over a period of time, which may be a two- to three-year period for large agencies, depending on staff availability and the number of intersections. It is advisable to document the progress in monitoring intersections throughout the jurisdiction.

Other types of roadway monitoring may be done by agency engineers, technicians, and sign maintenance or pavement marking crews while routinely driving the roadways within their agency. This is not a periodic or systematic monitoring of the roadway, as it simply involves agency staff being observant for traffic issues warranting further investigation as they drive to and from their destinations. Missing or severely-damaged STOP signs and other high-priority items should be addressed immediately.

Review of Crash Data

Another way to recognize if a problem may exist at unsignalized intersections is by reviewing crash data. This identification method should be part of an agency-wide safety information system. How such a system can be accomplished and how such data can be analyzed by a local agency are described in various materials from the FHWA Office of Safety:

- Road Safety Information Analysis: A Manual for Local Rural Road Owners

- Improving Safety on Rural, Local and Tribal Roads

- Developing Safety Plans: A Manual for Local Rural Road Owners

- Intersection Safety: A Manual for Local Rural Road Owners

An agency-wide review of crash data across all intersections will most often result in signalized intersections being at the top of the list of high-crash locations, due in large part to the higher traffic volumes typically associated with signalized intersections. Therefore, when ranking intersections by crash frequency, the intersections should be segregated into signalized and unsignalized groups. Crash data should be as recent as are available, and three years of data are desirable for analyzing most unsignalized intersections because of their relatively low frequency of collisions. At very low-volume intersections or when investigating bicycle or pedestrian crashes, a minimum of five years of crash data is generally preferred.

With quality crash and roadway data, agencies are positioned to conduct network screening to identify unsignalized intersections with the greatest potential for safety improvement. Network screening will allow users to define important safety criteria and improve the identification of potential safety improvements.

Spot maps can be developed using different colors or different size dots to identify where a cluster of crashes has occurred. In addition, in rural areas it is also useful to have a Complaint Spot Map because many rural crashes go unreported, but the driver involved will call the agency to complain about the conditions at the crash location. If the agency has its network on a geographic information system (GIS), then the basic crash/complaint data can be imported into that system and pin maps can be generated automatically. While computerized crash data are useful for identifying high-crash locations, individual police reports should be reviewed for accuracy, especially regarding the location and manner of collision.

In addition to total crashes, an agency may conduct a review of fatal and serious injury crashes to identify high-crash-severity locations. Separate analyses may also be done for pedestrian crashes or crashes involving bicyclists. An analysis of nighttime crashes will help to identify locations that would benefit from lighting installations or upgrades. Other factors to consider include crash patterns—such as right-angle collision types or collisions involving high speeds—that can help to identify a type of corrective action.

There is no set number of crashes that will indicate when an unsignalized intersection should be considered a high-crash location. Furthermore, the number of crashes used to identify a high-crash intersection within a jurisdiction may vary based on the crash reporting threshold and definition of intersection collision. An intersection collision in one jurisdiction may require the officer to indicate that the crash is “intersection-related,” while other jurisdictions may consider any crash within a set distance from an intersection (e.g., 150 feet or 250 feet) to be “intersection-related.”

Higher traffic volumes will generally result in a higher likelihood for a collision. A high crash rate—the number of collisions per year per unit traffic volume entering the intersection—may be more suitable grounds for identifying high-crash locations than considering crash frequency alone. To have an accurate crash rate, traffic volumes are needed for both streets. Because the number of vehicles entering an intersection is critical to its crash rate, even a single collision at a low-volume intersection may result in a high crash rate, which can be misleading in overstating the magnitude of a potential safety issue. A lack of recent traffic volume counts can be a major obstacle to developing accurate crash rates, especially in rapidly growing areas where traffic levels changed significantly over consecutive years.

If crash data are used to identify one or more high-crash locations, consideration should be given to identifying those unsignalized intersections that may have few or no crashes, but whose geometric and traffic volume characteristics are similar to the high-crash locations. This is particularly true for low-volume intersections and bicycle or pedestrian crash locations. In particular, bicycle and pedestrian crashes are rare relative to the total number of crashes that occur, so unsignalized intersections similar to the one at which bicycle or pedestrian crashes have occurred may benefit from the same treatment even though no crash has been reported there to date.

The existence of a single high-profile collision at an intersection does not necessarily connote there is a glaring safety problem at that intersection. While an agency should review serious injury or high-profile crashes, the occurrence of the crash does not always mean that corrective action is needed. At times, corrective action may be considered prudent to address the high emotions that result from a serious intersection crash. In this case, implementing a change or corrective action is not an admission that an intersection was previously “unsafe.” Furthermore, even a reasonably safe intersection may be improved to operate more efficiently or with a higher degree of safety.

2. Analyze the intersection.

Having become aware of a potential problem intersection, the next step is to analyze the intersection to confirm that there is a problem and to collect information that would clarify the type of problem and what might be causing it. This involves two activities: (1) an analysis of the crashes and (2) a site review and observation.

Crash data analysis

In the first step above, crash data were amassed to identify high-crash locations, recognizing that most unsignalized intersections do not have a high frequency of crashes due to lower traffic volumes. Now that a location has been identified as a problem unsignalized intersection, further investigation of the crashes—using at least three, and at times five, years of crash history—is recommended, depending on the type of analysis being conducted. The analysis would entail the following actions:

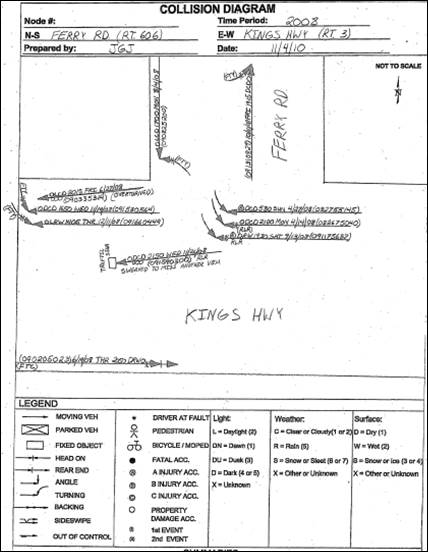

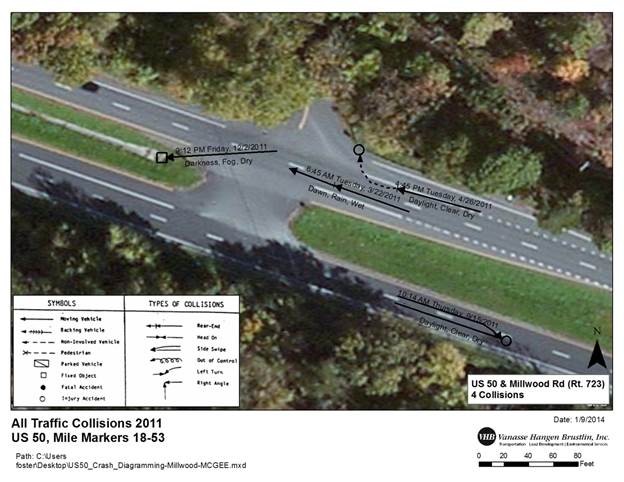

- Using information from individual crash reports, prepare a collision diagram showing where the crashes occurred on the approach and within the intersection. The collision diagram can be plotted simply on paper or over an aerial view of the intersection; both are illustrated below. The applicable state department of transportation may have software that facilitates the preparation of a collision diagram. With a collision diagram, the analyst can more readily identify where the safety issues are so that the manner of collision, directions of travel, and crash location can be identified for the site review.

- Develop tabulations of the crashes across several variables, such as the following:

- Day versus night—to identify potential issues with nighttime visibility.

- Day of week and time of day—to identify any certain times that appear to be more prone to crashes.

- Driver condition (e.g., alcohol impairment and seatbelt use)—to identify poor driver decisions or behavior that could potentially be addressed through enforcement or education initiatives.

- Driver age—to determine if younger or older drivers (or pedestrians) are overrepresented.

- Crash type—to determine if a certain type of crash is occurring more frequently than would be expected. The crash types that are likely to occur at unsignalized intersections include:

- Right-angle.

- Left-turn.

- Rear-end (major road).

- Rear-end (minor road).

- Sideswipe, same direction.

- Sideswipe, opposite direction.

- Head-on.

- Pedestrian.

- Bicyclist.

- Review the narrative discussion of the police report to better understand how and why the crash occurred. Usually, crashes occur due to a number of “contributing factors,” which can be categorized as human, vehicle, or roadway.

Example of a hand-drawn collision diagram. Source VHB.

Example of a collision diagram overlaid on aerial imagery. Source: VHB.

Site review and assessment

As a general practice, the analyst should visit the intersection to collect relevant information about its features and to observe traffic operations and other conditions at the intersection. This reconnaissance should be conducted at least during the days and times of day believed to be the most critical. Nighttime observations are always recommended for nighttime crash problems because deficiencies related to visibility of the intersection, the users, and certain characteristics of the traffic control devices can only be identified at night. Whenever possible, representatives of law enforcement and other stakeholder agencies should accompany the analyst in order to obtain multidisciplinary perspectives on the issues of concern.

If the intersection is considered to have a unique or high-priority problem, the agency may want to pursue a Road Safety Audit (RSA), which FHWA defines as a formal safety performance examination of an existing or future road or intersection by an independent, multidisciplinary team. It qualitatively estimates and reports on potential road safety issues and identifies opportunities for improvements in safety for all road users. More information about RSAs is available on the FHWA Office of Safety website.

The UIIG’s Assessment and Inventory Form was developed to provide guidance on the field analysis of an unsignalized intersection.

3. Identify treatment options.

Once the problem and its contributing factors have been identified, the next step is to identify treatment alternatives with the potential to address the problem. Upon conducting the analyses described above, the analyst may conclude that a certain improvement is needed. However, it is likely that more than one treatment could address the problem.

The main function of the UIIG is to describe the various treatments that can be applied to unsignalized intersections. A total of 75 treatments are described—71 that are engineering treatments, and 4 that are enforcement treatments. Education efforts may also be appropriate, and the activities that could be pursued are described, as well. Many of the engineering treatments are traffic control devices (i.e., traffic signs and pavement markings) that are included in the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) and discussed further in the UIIG’s What Does the MUTCD Say? and Types of Treatments.

The UIIG offers four ways in which the user can view the treatments from its Toolkit resources:

- By providing a few general inputs on the characteristics of the intersection in question.

- By selecting a problem type/treatment type combination of interest.

- By conducting a basic keyword search (e.g., “pedestrian”).

- By perusing the entire listing of treatments.

4. Select and implement the most affordable cost-effective treatments.

There will likely be several treatment options generated from the previous step. Some may be dismissed after reviewing the information provided in the treatment fact sheet and assessing the applicability of the treatment to the subject intersection. Cost estimates should be developed for the remaining treatment options. In doing so, consider not just the implementation cost but also any maintenance costs and the lifecycle of the treatment. The UIIG does not provide information on the costs of treatments. Depending on the treatment, installation and maintenance costs may vary widely across the U.S. and will depend upon the cost-accounting methods of the individual agencies.

Selection of the preferred treatment should take into account the expected effectiveness of the treatment. The measure of effectiveness may be potential crash reduction, operational efficiency, or simply adherence to a design standard or requirement. The safety benefits in the form of crash reductions have been established for several of the treatments noted in the UIIG, but even these are dependent upon various conditions that may not apply to the specific location being considered by the UIIG user. It is highly recommended that the analyst consult the Crash Modification Factors Clearinghouse to see if any of the treatments being considered have an established crash modification factor.

A crash modification factor (CMF) is a multiplicative factor used to compute the predicted number of crashes after implementing a given countermeasure at a specific site. The Crash Modification Factors Clearinghouse is a web-based database of CMFs and supporting documentation to help practitioners identify the most appropriate countermeasure for their safety needs.

Finally, since many of the treatments are low-cost traffic control devices that can be implemented by the agency staff or a contractor retained for such services, consider also applying these to other similar unsignalized intersections, even though not specifically identified as a problem area or “hot-spot.” Due to the inherent randomness of crashes, those along local streets and rural roads tend to be widely scattered across many roadway miles. For this reason, a hot-spot intersection emerging from one study may not be identified as such in a preceding or subsequent study because the crashes have randomly occurred at another intersection.

One way to address this phenomenon is to apply a systemic approach to safety—one that looks for the potential to implement improvements on a broader scale based upon combinations of risk factors that may increase the likelihood of a severe collision. The systemic approach focuses on a review of safety data beyond collisions: roadway geometry (e.g., number of lanes, median presence, skew angle), traffic volumes (e.g., approach volume, total entering volume), and other site characteristics (e.g., type of intersection control, presence of other traffic control devices). This method is proactive in nature and will identify locations for potential safety improvement regardless of whether their crash histories have placed them on a hot-spot list. Locations are targeted based on risk factors that may make them more susceptible to severe crashes.

See below for an example of how the systemic vs. hot-spot approach was used to apply a treatment.

STOP AHEAD pavement markings supplementing STOP AHEAD warning signs. Source: PennDOT.

An example of a treatment that may be applied in a systemic fashion is the STOP AHEAD pavement marking. This treatment is meant to increase awareness among drivers of impending stop control at an unsignalized intersection and comprises the installation of the words STOP and AHEAD in white thermoplastic material within the travel lane of the intersection approach under the control of a STOP sign. Scientific estimates of the treatment’s crash effectiveness suggest that this low-cost strategy can easily achieve a benefit-cost ratio of 2:1, especially at all-way stop-controlled and three-legged intersections (click here for more details). Being so low-cost in nature, an agency could apply the systemic approach to extend the application of STOP AHEAD pavement markings from a few hot-spot locations that emerged from a review of crash data to other intersections across the jurisdiction that share similar characteristics in terms of geometry and traffic volume.

More information on the systemic approach to safety is available via the following resources:

- A System Approach to Safety: Using Risk to Drive Action—a website within FHWA’s Office of Safety that describes the systemic approach to safety and includes a systemic safety project selection tool.

- Using Risk to Drive Safety Investments—a Public Roads article that describes how a systemic approach can help an agency get the biggest return for their investment in reducing crashes.

- South Carolina Case Study: Systematic Intersection Improvements—a description of statewide systemic intersection improvements implemented recently by the South Carolina Department of Transportation.

5. Monitor over time and evaluate the effectiveness of the implemented treatments.

The improvement process should not end with the installation of the selected treatment. An evaluation should be conducted to determine whether the treatment improved conditions at the uncontrolled intersection. If a lower-cost but less effective treatment was selected because of budgetary constraints, the agency should monitor the location to determine how well it has addressed the problem and determine if further improvements should be implemented. Simply relying on the “no news is good news” evaluation approach, while expedient, is insufficient. If the agency is following an overall safety improvement process like the one referenced earlier, it will be able to establish the treatment’s effectiveness with more certainty.

If the problem was brought to the agency’s attention by a citizen complaint or the police, then the agency should follow-up with these parties during the evaluation. The agency should ascertain if these groups believe the problem has been resolved. Furthermore, the individuals who identified the issue should be informed of the evaluation results.

Reporting verified favorable results of safety improvement to the jurisdiction’s political leaders may increase the likelihood of continued funding for additional improvements.

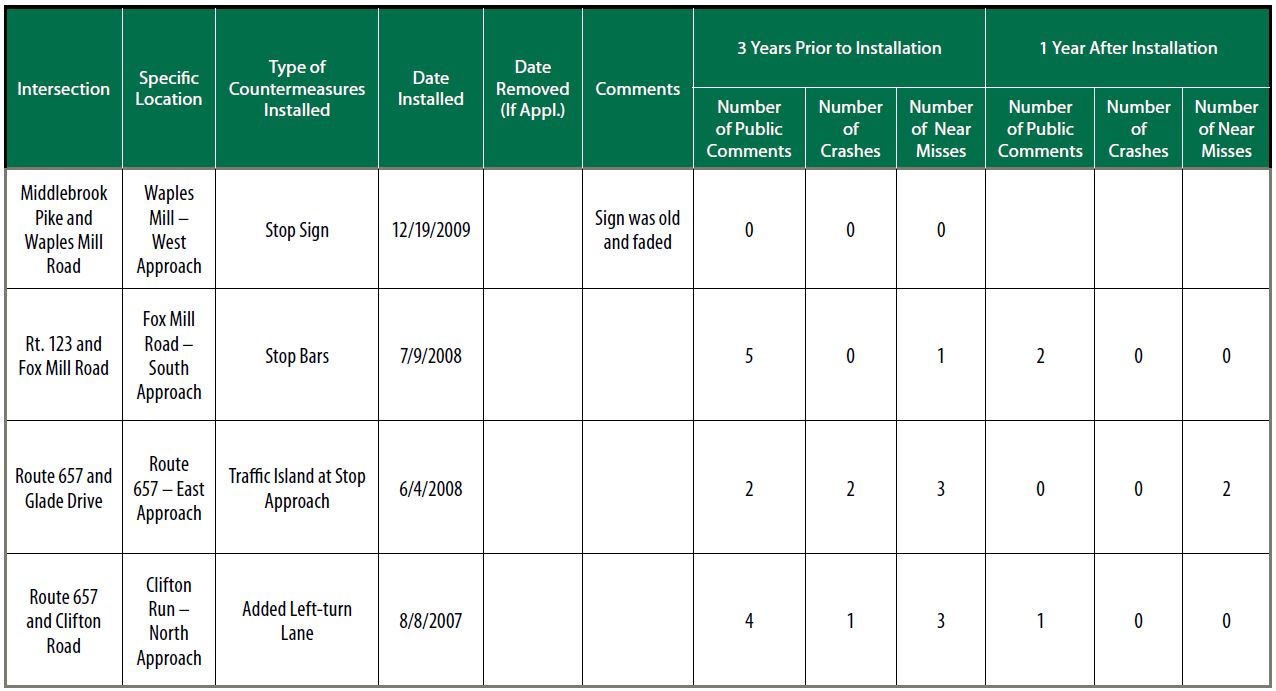

The table below shows one example of how an agency can monitor the effectiveness of a treatment. However, it is not a statistical-based evaluation. If a scientific evaluation is desired, the user should consult the AASHTO Highway Safety Manual or a qualified highway safety professional for more information.

Example Spreadsheet to Monitor Countermeasure Application History and Crash/Observational Data. Source: Ref: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/local_rural/training/fhwasa1108/

Additional Resources

The improvement process described above has also been presented in similar terms in numerous other guidance publications, including the following:

- Intersection Safety: A Manual for Local Rural Road Owners, FHWA Report No. FHWA-SA-11-08, January 2011.

- Road Safety Information Analysis: A Manual for Local Rural Road Owners, FHWA Report No. FHWA-SA-11-10.

- Highway Safety Manual, 1st Edition. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, 2010. (Refer to www.highwaysafetymanual.org.)

- Improving Safety on Rural, Local and Tribal Roads: Safety Toolkit, FHWA Report SA-14-072, August 2014. (This is a 3-volume series which can be accessed from the Office of Safety)